The Legacy of W. E. B. Du Bois

Check out this page for livestream links, press postings, and more relating to our upcoming concert on March 2nd! Tickets are available from the Box Office.

Click here to watch the livestream!

Press Clippings

Learn about the concert in the Harvard Gazette!

Explore the artistic nuts and bolts at the Boston Musical Intelligencer!

Delve into an inside perspective with a personal essay published by the Harvard Office for the Arts!

W.E.B. Du Bois

Last calendar year (2018) marked the 150th anniversary of the birth of the American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, author, writer, editor, and Harvard alumnus (AB, 1890) W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and completed his undergraduate studies at Fisk University. While at Fisk, Du Bois sang with and managed the Fisk Glee Club, developing an appreciation for music as an agent of social change that he would carry for the rest of his life. He matriculated at Harvard at 1888, where he was first forced to repeat his undergraduate education but eventually became the school’s first black recipient of a Ph.D. Although Du Bois was extremely successful in the academic realm and enjoyed close relationships with teachers, he felt alienated among his peers, saying that he was “in Harvard, but not of it.” Elaborating on this aspect of his experience over seventy years later, DuBois wrote the following:

“I sought no friendships among my white fellow students, nor even acquaintanceships. Of course I wanted friends, but I could not seek them… Only one organization did I try to enter, and I ought to have known better than to make this attempt. But I did have a good singing voice and loved music, so I entered the competition for the Glee Club. I ought to have known that Harvard could not afford to have a Negro on its Glee Club traveling about the country. Quite naturally I was rejected.”

After completing his Ph.D., Du Bois went on to become a titan in black thought and American history. In his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk (1904), Du Bois prophetically declared that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line. He went on to theorize the Veil, a sociocultural boundary that prevented white Americans from understanding black humanity. Trapped under the Veil, African Americans experience a “double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others… One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings…” Today, people often use use the term “code-switching” to describe Du Bois’ observation.

Beyond his writings, Du Bois was a potent activist who helped lay the groundwork for the next century of striving for black people in America and across the world. He was a vocal proponent and benefactor of black access to higher education, he co-founded the NAACP in 1909, and he was an early and lifelong participant in Pan-African conferences and causes. Du Bois eventually moved to Ghana and died there on August 27, 1963. A day later, Martin Luther King Junior delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington DC.

Making the Circle Wider

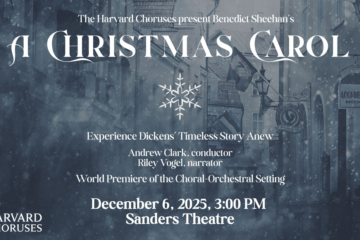

150 years after his birth, the Harvard Glee Club is holding a concert devoted to remembering and honoring Du Bois’ legacy. It will explore the man and the movement – a struggle toward African American equality that is older than America itself. To develop this concert, the Glee Club is working with Tesfa Wondemagegnehu, a composer, singer, educator, and activist who is renowned in the choral world for his work with African American spirituals.

Currently at St. Olaf College in Minnesota, Wondemagegnehu has worked with the Glee Club on every aspect of the concert, from arranging several of the pieces in the program to offering his renowned baritone voice to sing alongside us. He flew to Cambridge and rehearsed with the Glee Club in early February, leading discussion on the enduring relevance of African American spirituals and the importance of a candid dialogue around how privilege operates in choral music and art in general. He told the group that “Du Bois was not allowed to join the Glee Club. I was allowed [to work with you]. Now it’s my job to make the circle wider.”

A Tribute to The Souls of Black Folk

As a headnote to every chapter of The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois includes musical notation (without text) from a black spiritual as well as an excerpt from a European poem. By placing these two texts side-by-side, Du Bois calls on his readers to recognize not only that the two traditions are artistic equals but also to consider how, in putting the texts into conversation with each other, can expose the deeper resonances in each. Such examples thus present in literal terms the possibilities for reconciling the “unreconciled strivings” of the double-consciousness.

In tribute to Du Bois, the Glee Club will perform several of the spirituals he selected as his chapter headings. In place of excerpts from European poetry, we will sing a selection of choral pieces written by European composers that relate thematically to the spirituals. For example, the first section of the concert will open with a Kyrie written by the English composer William Byrd, who was forced to work in secret because of his Catholic faith. Following this work will be the spirituals “I’m a Rolling Through an Unfriendly World” and “Steal Away,” which advance the themes of oppression and secret resistance that began in Byrd’s mass setting. The concert will also feature brief readings by Harvard students and faculty, and there will be opportunities for the audience to participate in singing several songs.

“To Love”

“To Love,” written by Nathan Robinson ’20 as part of the Harvard Choruses’ New Music Initiative, is a choral setting of an episode presented in The Souls of Black Folk. The text is taken from a chapter entitled “Of the Passing of the Firstborn” which discusses the untimely death ofDu Bois’ infant son. The piece, possibly the first ever choral arrangement of prose texts written by Du Bois, deftly navigates a father’s complex emotions on the passing of a child. Du Bois saw his firstborn son as the next step in generations of dreaming and striving. In his infant cries, he heard “the voice of the Prophet that was to rise within the Veil.” At eighteen months old, Du Bois’ son contracted dysentery and as no white doctor would treat him, the child died after ten days of suffering. Du Bois fell into a deep despair, but ultimately found a strange comfort in his son’s death. As Robinson explains it, “Du Bois is shaken to the core… but at the same time experiences an ‘awful gladness,’ knowing that his child would not consciously suffer the horrors of his society.” In heaven, Du Bois knows his child is above the Veil and the color-line. He is “not dead, but escaped; not bond, but free.”

“Souls on Fire”

Well-known Harvard Faculty member and scholar Cornel West visited the Glee Club on February 17 to preview the concert (singing along side us) as well as to discuss Du Bois in all of his complexities and flaws. “Du Bois saw himself as a musician,” West reminded us. With regard to Robinson’s piece, Dr. West said that it was truly “historic.” He then read the following passage from The Souls of Black Folk: “Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope—a faith in the ultimate justice of things….sometime, somewhere, men will judge men by their souls and not by their skins. Is such a hope justified? Do the Sorrow Songs sing true?”

“You are answering that question,” West told us. “You are going to set people’s souls on fire.”